FAQs

What is the Griffin Warrior Tomb?

In May of 2015, our team made a shocking discovery near the Mycenaean Palace of Nestor. In an unassuming olive grove, we found an intact Mycenaean shaft grave containing hundreds of artifacts alongside the remains of a single male, the “Griffin Warrior.”

The grave’s discovery made international headlines. It was hailed as one of the most important finds in Greece in decades, and as conservation of the grave goods continues, we uncover new details about the warrior and his possessions. The 30- to 35-year-old man was buried with a set of bronze armor, armed with a gold-hilted sword, and surrounded by dozens of sumptuous items including intricate gold rings and a remarkable carved sealstone, the Pylos Combat Agate. Researchers have reconstructed the man’s facial structure and are currently assessing his genetics. Meanwhile, conservators continue to piece together the grave goods, many of which were crushed over the centuries by the weight of soil and a large stone that once covered the tomb.

What is a Tholos Tomb?

Tholos tombs are large, beehive-shaped tombs built into slopes of hills. In Mycenaean times, the bodies of elites were placed in the center of the tomb along with precious grave goods, and after the funerary ceremonies, the mouth of the tomb (“stomion”) was closed with a wall of stones, the blocking wall, which separated the interior of the tomb from the exterior entryway, the dromos. When it came time for another funeral, the blocking wall was removed, the remains of the previous burial were swept to the side and the accompanying grave goods were recycled.

Near the grave of the Griffin Warrior are three tholos tombs. These include Tholos IV, which was discovered and excavated by a team directed by Dr. Carl Blegen and supervised by Lord William Taylour in 1953, as well as Tholos VI and Tholos VII. Our team discovered the latter two tholoi in 2018, and our excavation of them is ongoing.

What is the Combat Agate?

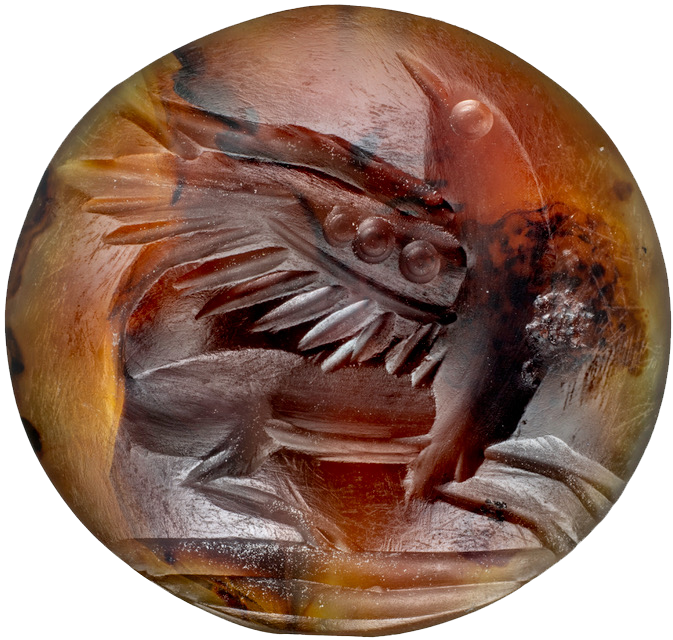

When the grave of the Griffin Warrior was discovered, all of the grave goods that had been buried with the deceased man were still in the tomb. One of the most fascinating of these items is a small sealstone known as the Pylos Combat Agate.

Mycenaean sealstones are tiny, intricately carved stones that were either used as personal seals or kept as precious goods. The Combat Agate, which was produced on the island of Crete around 1450 B.C., is particularly intricate. On its surface is a carving of a warrior vanquishing two foes, all of whom have remarkably detailed clothing, hairstyles, and muscles. It continues to stun to this day. When the Pylos Combat Agate was announced in 2018, it was heralded in headlines around the world.

What is the Hathor Pendant?

In 2018 in a field near the Palace of Nestor, our team unexpectedly discovered two tholos tombs. As we continue to excavate these tombs, we have uncovered dozens of items that were buried in them alongside wealthy Mycenaeans. One of the most fascinating objects uncovered from the tholos tombs has been a pendant depicting the Egyptian goddess Hathor.

The Hathor Pendant, as it is known, was discovered in the dromos of Tholos VI, the larger of the two tombs. Its depiction of Hathor, who has distinctive, cowlike ears and symbolizes fertility, points to Late Bronze Age trade links between Greece and the Near East. It is the only known image of an Egyptian deity at Mycenaean Pylos.

Since its announcement in 2019, the pendant’s discovery has been hailed by archaeologists and art historians alike.

What is the Bay of Navarino?

Our work and daily life at the excavation geographically surround the Bay of Navarino. Although our research focuses on the history of the area from the Bronze Age, the bay has played stage to a host of significant historical conflicts.

Due to its strategic position on the western edge of the Peloponnese, the Bay of Navarino has been contested for millenia. The island of Sphacteria, which runs most of the length of the bay and serves as a natural barrier to the sea, has often been caught up in conflict as well. From the Battle of Pylos (425 B.C.) between the Athenians and the Spartans to the Battle of Navarino (1827 A.D.) during the Greek War of Independence, many groups have fought in the bay, including the Byzantines, the Venetians, the Ottomans, the Egyptians, the French, the Russians, and the British.

Remains of the bay’s many eras of history are still present today. The bay’s name, Navarino, is the same as the name of Pylos when it was ruled by the Venetians, and there are 89 shipwrecks in the bay, the most recent of which is from the 1980 wreck of the oil tanker Irene’s Serenade.

Here is a map of Sphacteria and the bay: https://goo.gl/maps/CujLy7UYzq5acpE59

What is the Palace of Nestor?

Our current excavation lies in the vicinity of the Mycenaean Palace of Nestor. Palaces like this one were key elements of the power structure in Greece during the Mycenaean period, which spanned the latter part of the Bronze Age from around 1600 to 1100 B.C. At the time, seats of power centered on palaces that were headed by leaders known as wanakes and surrounded by settlements. Many of these palaces were located near the coast and, because of the mountains common throughout the Peloponnese, accessible mainly by water.

In 1939, a joint American-Greek excavation headed by Dr. Carl Blegen and Dr. Konstantinos Kourouniotis discovered one such palace on “the shores of sandy Pylos,” which is mentioned in Homer’s Odyssey as belonging to King Nestor. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, teams headed by Carl Blegen from the University of Cincinnati excavated the palace as well as the surrounding acropolis. One of their most significant finds was a cache of tablets inscribed with Linear B script, an early form of written Greek, which contributed to the script’s eventual decipherment. Portions of the palace were recently excavated again to prepare for the construction of a large roof and elevated walkway, which protects the palace from the elements and provides visitors with a view of the site from above.

Who were the Mycenaeans?

Greece holds clues to a rich diversity of historic civilizations. Our work focuses on material left by Mycenaeans, a group of people who lived in Greece from 1600 to 1100 B.C. during the latter part of the Bronze Age, or Helladic Period.

Mycenaeans were incredibly sophisticated in many aspects of life. Their government centered on a set of palaces which oversaw whole regions of people, and their trade network extended across the Mediterranean, including a close association with the Minoans on Crete. They were skilled engineers and built many of their structures in cyclopean stonework, a form of masonry that uses large, uncut boulders.

Mycenaean society was warrior-focused, included various religious cults, and abided by a hierarchy of classes and labor. Much of what is now known about Mycenaean life is linked to records written in the ancient Greek Linear B script and preserved on clay tablets at various Mycenaean sites, including the Palace of Nestor. The memory of Mycenaeans is particularly strong in ancient Greek mythology and literature.

Who was Carl Blegen?

Within the field of Classics, Carl Blegen looms large as one of the foremost American scholars. Born in 1887 in Minneapolis, Minnesota, he was raised by his Norwegian immigrant parents in a strict Lutheran household. As a young adult, he earned a bachelor’s degree at the University of Minnesota, completed his graduate studies at Yale, and served as the secretary, then assistant director, of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens from 1920-1926. During this time, he participated in multiple excavations in Greece and laid the foundations of his long term relationship with his wife, Elizabeth Pierce, and the archaeologist couple Bert Hodge Hill and Ida Thallon. For the next three decades, Blegen served on the faculty of the Department of Classics at the University of Cincinnati, where he retired as head of the department in 1957.

Among Blegen’s accomplishments are the discovery of the Palace of Nestor and its subsequent excavation as well as extensive excavations at Troy. For his work, he was awarded multiple honorary degrees and awards and currently has two libraries named in his honor, one at the University of Cincinnati and another at the American School.

Who was Marion Rawson?

Marion Rawson served as a core team member during Blegen’s excavations of the Palace of Nestor and was a co-author of the primary publications about the site.

She was born in Cincinnati’s Clifton neighborhood in 1899 to a wealthy family who embraced European travel, museums, and music. From 1918-1922, she studied psychology, economics, and politics at Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania. Upon her graduation, she returned home to care for her mother and began courses in archaeology, English, and, eventually, architecture at the University of Cincinnati. After her mother’s death in the late 1920s, this coursework extended into fieldwork as Marion, in many cases alongside her sister Dorothy, began joining excavations headed by Carl Blegen.

Rawson established herself as one of Blegen’s principal team members during the excavations at Prosymna, and from 1932 through 1938 she played a significant role in the work at Troy. From 1953 until 1964 she excavated at Pylos. She was heavily involved in compiling and editing the final publications for the Troy and Palace of Nestor excavations and was a co-author of the Pylos publications. In all of her archaeological work, Rawson was known for her impressively thorough documentation, peacekeeping among team members, academic humility, and organizational skills.

View some of the Cincinnati sites that were familiar to Marion Rawson: https://www.google.com/maps/d/edit?mid=1amsJwZiFgePM8oqLAF0u5esUsnaF2YBM&usp=sharing